State archaeologist Dr. Mary Beth Trubitt presented a program Friday morning about the art of Arkansas' earliest residents for guests of the Dallas County Museum, 211 Main St. in Fordyce.

The program, titled "Ancient Caddo Artists and their Descendants," explored the history of centuries-old ceramic artifacts created by regional Native American people along with the evolution of contemporary Caddo artists.

Trubitt is the Arkansas Archaeological Survey's Research Station archaeologist at Henderson State University in Arkadelphia. She shared how Henderson State University has a large collection of Caddo artifacts.

In her first return to the museum since 2011, Trubitt began by saying, "I'm happy to be back in Fordyce. You're always so welcoming. I need to come back more often." More than 40 attendees were on hand to hear Trubitt's talk.

"Caddo pottery goes back 3,000 years during an era ranging from 1000 B.C. to 1000 A.D.," she said, going on to explain that their society was agriculturally based and that they settled in the Arkansas River valley and along the Red, Sabine, Angelina, Neches, Ouachita and Saline rivers.

Due to the nature of where many archaeological digs are discovered, such as recent construction sites, people rarely find whole pots, only shards of broken vessels. Even so, the unique shapes, patterns and ornamental designs on the remains tell volumes about where they fall in that 3,000-year period.

"Even though we find different treatments, on different vessels for different purposes," she said, "Caddo had definite cultural rules for decorating pottery. There is a very finite spectrum of designs. I'm currently working on a compendium for compositions found mostly in Arkansas."

Through these designs, archaeologists can narrow down a time and place by looking at their particularities. In some cases, they can even recognize the work of a specific potter or a community of potters replicating a chosen design in detail. Different schools of design range from simple and straightforward to the quite complex.

"It's not always so easy to recognize one tribe's pottery from another, especially along border areas where tribal territory overlapped," Trubitt said. "With the movement of the Spanish through Arkansas in the 1500s, it created some disruption among certain areas of population."

Survivors of epidemics and violent encounters were forced to incorporate into other tribes, bringing their unique perspectives to create blended styles, she said.

"We can also source locations of clay deposits to determine exactly where the origin of a pot is derived," she said.

Turning her attention to the Caddo people in current times, Trubitt said, "Most Caddo reside in Oklahoma today. The Caddo Nation has a language preservation program to teach their language to young people and adults."

Because much about a people's culture is preserved through language, the Caddo desire to keep the language alive in an effort to preserve their heritage and history, she noted.

Regarding the community of Caddo artists in Oklahoma today, Trubitt said, "I like to support contemporary Caddo artists and I have many of their pieces in my home."

She shared how they now work in a range of mediums from graphic design to stone sculpture and ceramics. Their art is seen at museums, exhibits and shows across the country and are available online. Some of the more widely recognized Caddo artists include Chase Kahwinhut Earles, Jennifer Marie Reeder, Jeri Redcorn, Raven Halfmoon, Yonavea Hawkins, Chad Nish Earles, A. Wayne Tay Sha Earles and Delores Perkins.

"They utilize traditional designs as well as incorporating traditional designs into more modern motifs," Trubitt said. She went on to say that many artists are making ornaments as regalia to be worn in traditional social activities and ceremonies.

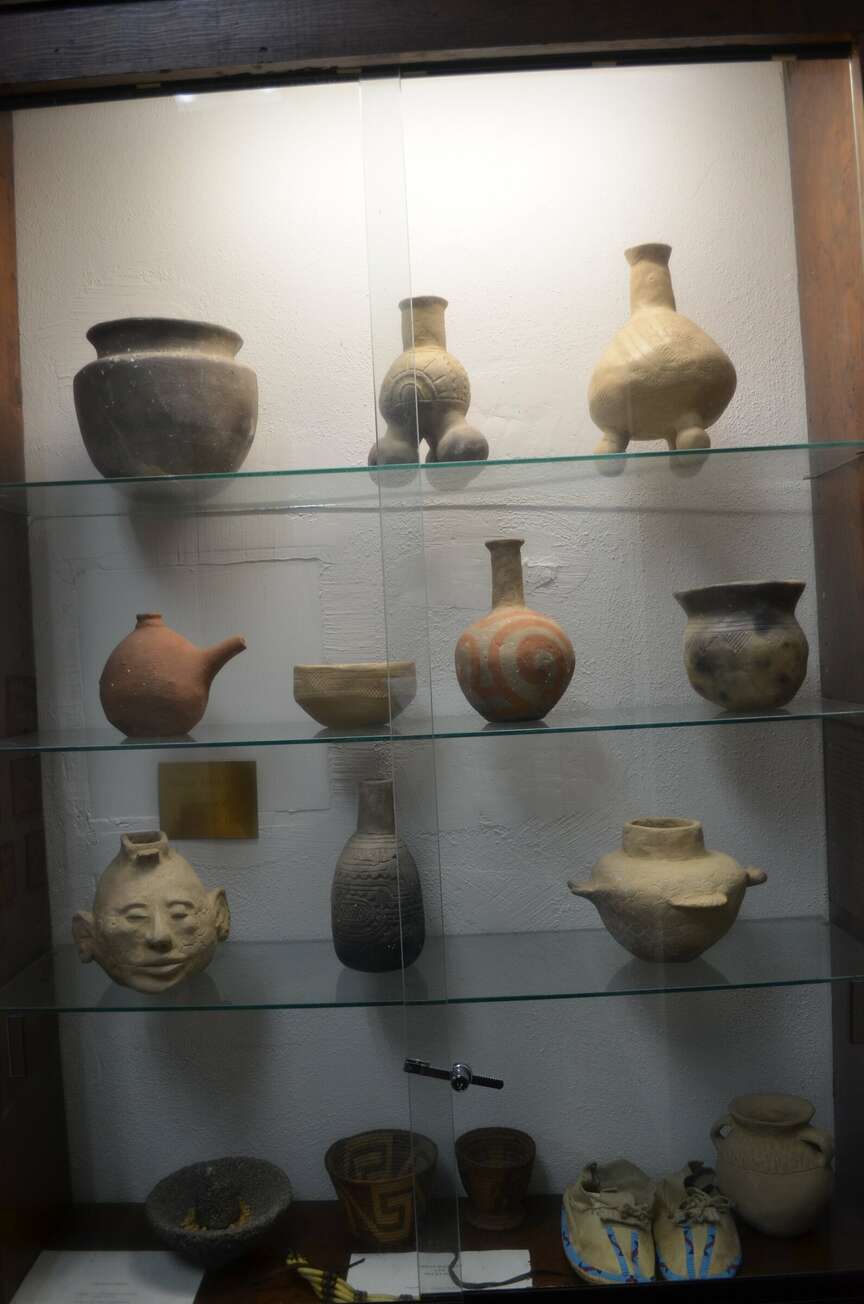

After the lecture, Trubitt led guests into an adjoining display room to view the museum's extensive collection of pristine Caddo pottery while answering questions from her audience. During the Q&A, Trubitt addressed a significant change in the making of utilitarian pots. In the 1300s, Caddo potters switched from "grog" temper to "shell" temper, replacing the mixing of broken ceramic shards into the fresh clay before firing to using crushed mussel shells instead. Incorporating shells into the mix gave cooking pots more resistance to thermal shock, making them less likely to fracture over the cooking fire.

After the program, the museum was open for tours with snacks and beverages provided.